Disinformation is always on the move. At first you could simply avoid offending sources, but new tactics have complicated matters, further blurring the information landscape. Here at Factal, we’re tracking several trends heading into 2020:

1. Governments as arbiters of truth

Global governments are investing in their own efforts to identify disinformation, challenge claims and urge citizens to stick with official sources. While beneficial in some cases to protect the public – which justifies the funding – these efforts can introduce challenges of their own by belittling or bypassing the media, creating government disinformation and stifling free speech. In India, government social monitoring teams watched for “hate speech and misinformation” tied to the Supreme Court Ayodhya verdict, and police warned citizens of possible arrest if they create “communal disharmony” online. In the Philippines, the government accused the media of misinformation in its coverage of the Southeast Asian Games, launching its own propaganda campaign and warning critics of the games that they may be charged with sedition. This year a record 30 journalists have been imprisoned for spreading “fake news” as defined by governments, according to the Committee to Protect Journalists.

2. Partisan and impostor fact-checkers

While governments increasingly aim to define the facts – often in the name of public safety – partisan fact-checkers aim to advance their political goals. Last month the UK Conservative Party changed the name of its verified Twitter account to “factcheckUK” (below) during an election debate, declaring its candidate Boris Johnson the “clear winner.” Earlier this year, Mexico’s president created his own fact-checking service, “Verificado Notimex,” which was named similarly to the independent service, “VerificadoMX.” While rather blatant, you can expect more nuanced efforts to create biased fact-checking services in the months to come. “If people start to believe that fact-checking can come from partisan sources, they no longer have reason to believe it,” explains Poynter, which runs the International Fact Checking Network (IFCN).

3. Information DDoSing

In cybersecurity circles, a denial of service (DDoS) attack is a malicious attempt to overwhelm a server or service with a flood of internet traffic. In the human world, we’re already flooded with information, choking social feeds and inundating news cycles. Injecting mass amounts of dubious, conflicting arguments on top of all this noise has a debilitating effect – especially when firing from different sources all at once. “Flooding an information space with conspiracy theories is like pumping static into your living room,” explains Kate Starbird, a disinformation researcher and professor at the University of Washington’s Center for an Informed Public. “It prevents you from focusing on the truth.” Now a proven method, stay tuned for more DDoSing in 2020.

4. Readfakes

You’ve heard of deep fakes (more on that below), but the term “readfakes,” coined by Graphika’s Camille François, refers to using technology to generate “believable and engaging” text at scale – not just on social media, but across websites and newsletters. Not only does this contribute to the DDoS effect, but it gives artificial credence to information. “We’ve already seen how copied-and-pasted text spread across multiple and diverse ‘news’ creates a kind of astroturf that may trick our brains into thinking we’re triangulating,” explains Starbird. “When that text can be auto-generated (and varied) that effect will be even more powerful.”

5. Disinfo aimed at counter-disinfo efforts

This is an age-old tactic that has modernized in the digital age. Take the White Helmets, the Syrian volunteer rescue workers that are credited with saving countless lives. When the group put cameras on helmets and began to videotape its response to bombings, it disproved the government’s narrative with hard evidence. In return, the White Helmets have become a target of both Syrian and Russian disinformation efforts that claim it’s a terrorist organization. It’s a similar story for Bellingcat, the collective of OSINT (open source intelligence) investigators that have become a Russian disinformation target. They’ve been accused of faking images, hacking servers, collaborating with terrorists and being infiltrated by the FSB, the Russian Federal Security Service. There are also more subtle efforts, such as troll/bot Twitter accounts proactively blocking a well-known disinformation researcher.

6. Narrative laundering

Another longstanding technique has been updated for the internet age. Narrative laundering is “moving a certain narrative from its state-run origins to the wider media ecosystem,” explains the Stanford Internet Observatory. The process begins with state-created think tanks and media arms that author the narrative, hoping that friendly media sites will pick it up. Then the picked-up story is distributed by a network of accounts across various platforms, giving it more credibility. “Traditional and social media are intertwined in a manner that makes spotting and stopping the viral spread of propaganda difficult,” the Observatory continues, warning of more narrative laundering in the 2020 election. A less nefarious variation: a social media rumor that makes the jump to legitimacy when a public official mentions it in the media.

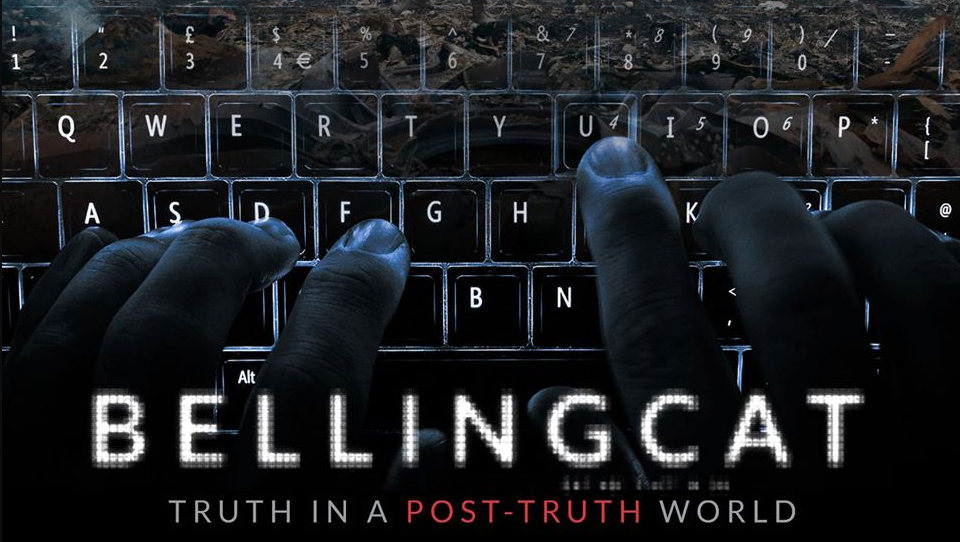

7. Targeted internet outages

Shutting off the internet is a government tactic to attempt to stop the spread of a popular uprising. Historically, this is a rather crude method that typically leaves plenty of gaps. Iran’s shutdown in November “is one of the most complex we’ve ever tracked,” said Alp Toker, director of NetBlocks. Not only did it achieve a near “wholesale disconnection” among the population, it retained access to Iran’s National Information Network, its centralized internet. “Nobody is online except pro-regime activists,” noted one Iran watcher, giving the outside world the false impression that normalcy had returned. As governments build out more of their own network capabilities, these targeted outages will become more the norm.

8. Private groups

Identifying and avoiding disinformation on public feeds is hard enough, but private groups and conversations reach a new level of difficulty. One of the world’s largest social platforms, WhatsApp, has long battled mis- and disinformation. “With no way of accessing the encrypted data, and no way of identifying the original sender of a viral message that’s been forwarded countless times, the platform has been a frustrating conundrum for fact-checkers and misinformation researchers alike,” writes Poynter’s Daniela Flamini. It’s also a powerful method for narrative laundering. With Facebook’s goal to become a “privacy-focused communications platform” across the board, this conundrum shows no signs of abating.

9. Deepfakes

We’d be remiss if we didn’t mention deepfakes, those seemingly-real fake videos and photos created by AI algorithms. While deepfakes are certainly a longer-term threat on the horizon, they’re attracting a disproportionate amount of attention compared to the shorter-term trends we list here. “Deepfakes are the ultimate ‘shiny object’ in all disinformation discussions,” tweeted Nieman Lab’s Josh Benton. But it’s a trend worth watching as technology continues to improve.

10. Partisan local news sites

As local newspapers continue to struggle in the United States, new networks of local “news sites” seek to fill the void with point-of-view coverage. Democratic strategist Tara McGowan has created Courier Newsroom, a network of digital newspapers (like “The Dogwood” below) located in swing states designed to counter conservative news coverage. “Amid all these fake news and misinformation channels, we’re just not reaching people with the facts,” McGowan said about the launch. Meanwhile in Michigan, nearly 40 websites with names like “Lansing Sun” and “Ann Arbor Times” offer right-leaning stories with apparent funding from conservative sources. These networks join the existing fray of fake news clickbait sites preying on readers’ trust in local news.

11. Professionalization of disinfo

Disinformation was once the product of shadowy groups in a handful of countries, but it has exploded in the last three years. A study (.pdf) by the University of Oxford found “evidence of organization social media manipulation campaigns” have taken place in 70 countries this year, up from 28 countries in 2017. This isn’t just governments, but organizations like the Israeli marketing firm Archimedes Group that had “targeted at least 13 countries” on Facebook, according to DFRLab, which called it “a troubling sign that highly partisan disinformation is turning into a capital enterprise.” As these efforts become professionalized, they also become more sophisticated and spread quickly from country to country.

If you feel your blood pressure surging after reading the list, you’re not alone. These tactics often overlap, and they’re continually changing. But we’re optimistic about the future, thanks to the growing army of fact-checking and verification efforts around the world. If you have any trends to add — or any feedback — please drop us an email.

Cory Bergman (@corybe) is the co-founder and VP of product/news at Factal, a breaking news verification platform relied on by many of the world’s largest organizations. Previously, Cory was co-founder of Breaking News at NBC News, the first and largest real-time verification effort in journalism. Top photo by Elijah O’Donnell on Unsplash.