By Cory Bergman and Imana Gunawan

Myanmar’s military junta doesn’t want the story to be told. Since the early-morning raid on Feb. 1, 2021, during which the country’s senior elected leaders were detained, security forces have shot protesters, arrested journalists, shuttered newsrooms and shut off the internet. They’ve engineered their own narrative in an attempt to discredit the election and downplay the protests. But thanks to its citizens, Myanmar’s story is still reaching the rest of the world.

Since those first early hours, Factal’s verified coverage has flowed into operation centers at the largest international NGOs, global companies and technology platforms grappling with the bloody coup. NGO workers are hampered by threats, a lack of cash and an intensifying pandemic. Companies are contending with national strikes and the safety of their staff. And technology platforms are in a constant battle against mis- and disinformation and human rights abuses. Facebook, YouTube and Twitter have all suspended Myanmar military accounts.

Like most news organizations, Factal is covering the story remotely, relying on Myanmar’s citizens and journalists to provide on-the-ground reporting over the internet. In an attempt to mute protests and news coverage, security forces cut the internet every evening after companies close for the day. Myanmar’s more tech-savvy citizens have skirted the outages through VPNs and a new messaging app called Bridgefy, which uses Bluetooth rather than the internet to communicate. But most are left in the dark until authorities restore access in the morning. The ensuing burst of information is challenging to parse, but provides a much-needed look at the previous night’s violence and intimidation.

Together with the outages, longstanding news sources have been silenced. As of March 17, operations at all independent newspapers have been suspended. Several dozen journalists have been arrested, but many others continue to publish online in hiding. A handful of independent news sites, including Mizzima and Myanmar Now (below) are still in operation. As the AP’s Elaine Kurtenbach explained, “Myanmar seems to be reverting to its old system where officially sanctioned media are entirely state-controlled, as they were before August 2012.”

With fewer trusted journalists in the mix, eyewitnesses have been filling the void, videotaping the violence on their phones and sharing clips online. To verify posts, Factal’s newsroom begins by backtracking eyewitness reports to their original source. While videos are easy to find on Twitter and YouTube, most are pulled without attribution from Burmese pages on Facebook – Myanmar’s dominate social platform.

The situation becomes more complex outside the spotlight of the major cities like Yangon, Naypitaw and Mandalay. Coverage is sparse, crackdowns can be more violent and local languages are not compatible with mainstream translation services like Google Translate. Myanmar’s rural populations may also be affected by various armed conflicts or insurgencies that span decades as part of the country’s civil war. These insurgencies not only affect people’s ability to protest or dissent, but also for local media outlets to adequately report on events.

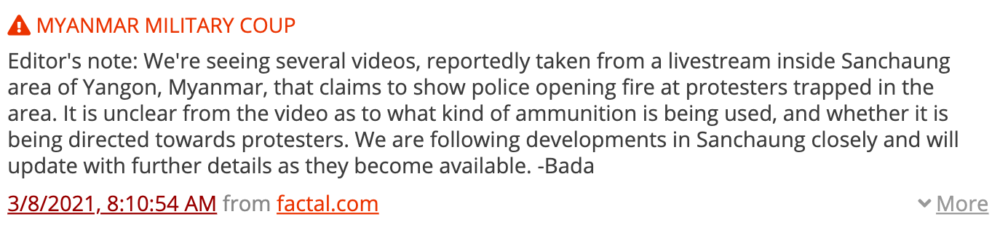

Factal’s sustained focus on the Myanmar coup – we’ve published more than a thousand verified updates since Feb. 1 – has helped our newsroom to establish known on-the-ground sources with a consistent track record. By corroborating details between them, editors are able to provide a reliable picture of what’s happening. When the sourcing or details are not clear – such as confusion between live rounds and rubber bullets – we post editor’s notes (below) to provide context and strike a balance between speed, accuracy and transparency.

The big question is where does Myanmar go from here. The military shows no signs of stepping back, outside diplomatic efforts have fallen short and the world’s attention won’t stay focused on Myanmar for much longer.

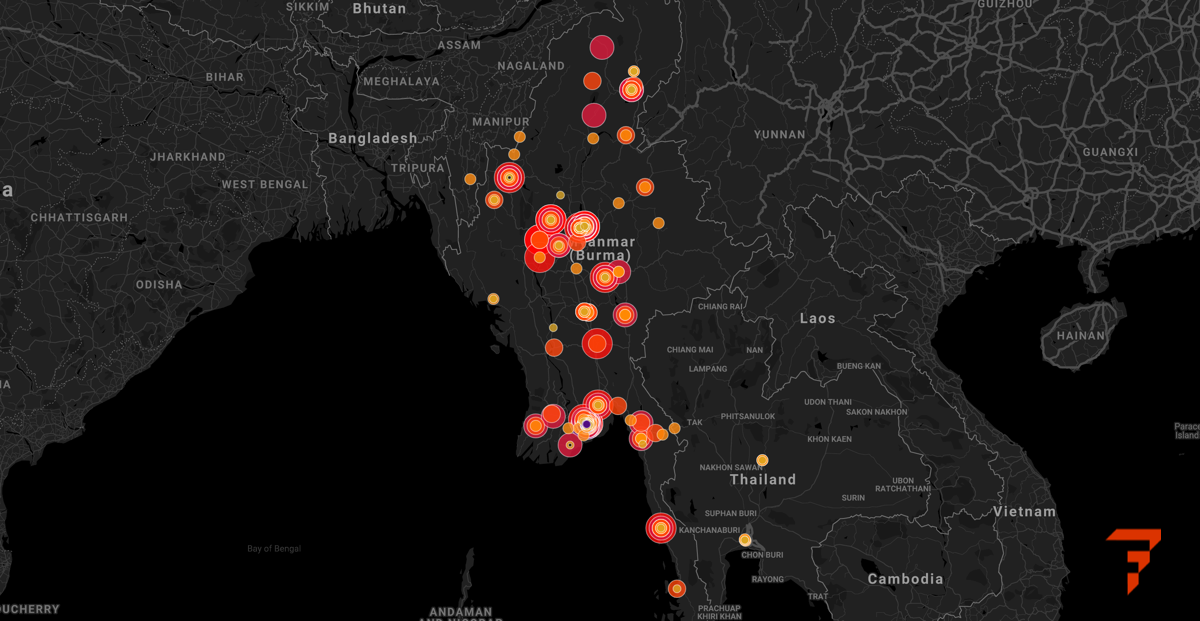

(Factal is a breaking news verification, alerting and mapping platform for global organizations. NGOs have free, unlimited access. Image above shows recent Factal coverage of the Myanmar coup.)